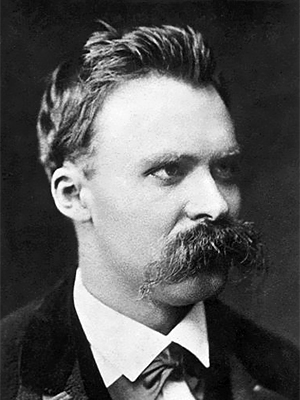

In early January 1889, the great philosopher Nietzsche showed the first signs of the madness that marked the last part of his life. He was living in Turin at the time and wrote a series of letters and notes, known as the ‘madness letters.’

The issue of Nietzsche’s madness is still open, because although it is clear that the philosopher suffered from it, it cannot be said when it began and how (and if) it influenced his philosophy, which is certainly one of the most important for its depth of vision on the human condition and sincerity towards established civilization.

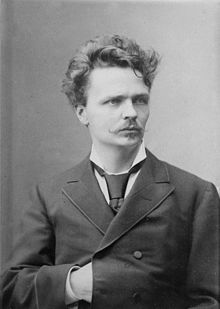

Among the various notes he wrote, in which he signed himself alternately as Caesar, the Crucified, Dionysus, Antichrist, and so on, believing himself to be the prince of princes and particularly targeting the noble representations of the historical Germanic hierarchies, there was also a postcard addressed to the poet and playwright August Strindberg, with whom he had an important correspondence. In it, he wrote:

‘Herr Strindberg: Eheu! No more! Divorçons!

The Crucified’

It was a sign that madness had now taken over, yet even in his madness, it is possible to see the signs of a profound gaze, because if every madness is grasped in its a-spatial and a-temporal aspect, there is the possibility of discerning underlying secrets of the entire, always one and unified reality, beyond the division in which the existence of the entire world is cast. In 1883, August Strindberg was in Paris, where he himself was starving and stubbornly trying to alchemically make gold in a hotel room, attached to a crucible and prey to a mental alteration that for some was madness.

August Strindberg was in a very difficult artistic period, due to accusations of antifeminism, misogyny, and blasphemy provoked by his latest works. In 1886 he wrote ‘Camerati‘ (the first title was ‘Predatori‘), which was heavily criticized for its exaggerated antifeminism, followed in 1887 by ‘The Father,’ in which a family father is increasingly questioned by his wife about the education of the daughter, until he seems – and becomes – mad. The theme of madness, here it is again. In 1888 there was ‘Miss Julie,’ which brought him worldwide fame.

Here is the plot that shocked Swedish society: ‘Julie, a twenty-five-year-old count’s daughter, spends Midsummer’s Eve at the servants’ party, while her father is away. She tries to seduce the young servant Jean, who declares himself in love with her. Seen by the servants, they decide to flee for the imminent fall of the girl’s reputation, but they are discovered by the cook Kristin and fail to do so. When the count returns, Jean feels guilty and, declaring that the respect and subjugation he feels towards him prevent him from contradicting him, suggests to the girl to commit suicide by handing her a sharp razor to achieve the purpose.’

In 1877, Strindberg had married the Finnish-Swedish actress Siri von Essen, with whom he had three children, but their relationship deteriorated more and more, until they became similar to those Strindberg described in his dramas and novels. These last dramas were inspired particularly by the naturalism of Emile Zola, who literarily proposed the ambitions of positivism: the human being was to be observed like any other natural phenomenon, and therefore considered an animal like others, and all its manifestations were read according to scientifically predictable laws. The same positivism that inspires the protagonist of ‘The Isle of the Dead,’ Andrea Nascimbeni.

Here is what Strindberg wrote in the preface to his ‘Miss Julie’:

A day will come, however, perhaps, when we are so advanced, so enlightened, that we can observe with indifference the brutal, cynical, cruel spectacle that existence offers us. Then we will have disarmed the inferior and unreliable instruments of thought called feelings, which have become superfluous and harmful to the maturation of the judgment tool.

And it was precisely to the Isle of the Dead that Strindberg himself set sail, through a binary experience that he was not the only one to experience in front of one of Arnold Böcklin’s paintings. On one hand, this experience resulted in an unfinished chamber drama of 1907, precisely ‘The Isle of the Dead,’ which envisioned Böcklin’s painting as a stage backdrop, on the other hand, in front of that painting he himself had lived another moment of estrangement, affected by the famous Stendhal syndrome. As for the drama, the show was presented for the first time on January 21, 1908, at the Intima Theater in Stockholm, Strindberg’s theater. However, for unknown reasons, it was performed only twelve times. The modernist and abstract structure of the work probably contributed to its not immediate success. Unfortunately, there are no photos, program notes, or the like preserved from the original set of the staging.

Interesting, however, is the subject of the drama. It tells of a student who is able to see the dead.

Scrivi una risposta a Paths to the Isle of the Dead – 2 – Lenin and Hitler – Fabrizio Valenza – Immaginazioni, scritture, filosofia Cancella risposta